by Laura Fisher

This blog post has been a long time coming! In September last year Jono Bolitho and I had another residency at Glenn Morris’ farm Billabong in Inverell for two nights.

During this visit, we roamed around the farm, discussing the properties of humus and the lessons we’d learned from presenting our prototypes at Siteworks. We continued to ponder a question that has troubled us from day dot: should we aim for scientific accuracy in our humus model or take full artistic license to communicate the complexity of this substance? As we looked over textbook diagrams of microbes and protein clusters, we realised that if we took the scientific route, we’d get bogged down in technicalities and lose our way (and potentially our audience). In any case, there are still many unsolved mysteries in the world of humus science. As Glenn keeps reminding us, we want to get away from the idea that humus has to be verified through existing scientific lenses before we can protect it and cultivate it as a society. This is a fascinating problem that remains a huge obstacle for the regenerative agriculture movement.

We then crossed one of those conceptual thresholds that makes the collaborative creative process so exciting. The simple realisation was this: humus is the ideal environment for the tiny life forms that inhabit the soil. It’s comfortable and sustaining, it’s where they belong. Degraded soils on the other hand are places that are horribly inhospitable to life, fatal in fact. Those lifeforms that don’t die retreat to find somewhere better to hang out.

So moving between degraded soil and humic soils, we thought, might feel a bit like standing in the scorching heat and harsh light of a heatwave day, out in a baked paddock where nothing dares to grow, and escaping from that into a cool, damp sanctuary, in which we would feel soothed and replenished.

Florence Reid in a bamboo bush-house at Bainagowan Station, ca. 1900. Sourced from the enclos*ure blog

As we imagined what such an oasis might look like, and wondered how we could build it, Jono meandered around the internet for inspo. He discovered a marvellous piece of history at Cynthia Goodson’s enclos*ure blog: the turn-of-the-20th-century Australian tradition of creating “bush houses” for ferns and other tropical plants. The bush-house, Goodson writes, “was modelled on the English glassed-in greenhouse or conservatory, but built with less costly, local materials.” Sometimes they were part of people’s verandahs, and Goodson reckons they were often “used as cool(er) places to entertain and relax.” What a striking thing: a vernacular adaptation of a hothouse, which in Britain created a warm humid environment for tropical plants, to a coolhouse, a shaded place full of plants where people wearing ridiculously inappropriate Victorian clothing could find respite from the heat of the Aussie summer.

Bush- or shade-house at Toowoomba residence, Roslyn, ca. 1900. Sourced from the enclos*ure blog

Fernery in the Clayfield residence, Elderslie, in the Brisbane suburb of Clayfield, ca. 1900. Sourced from the enclos*ure blog.

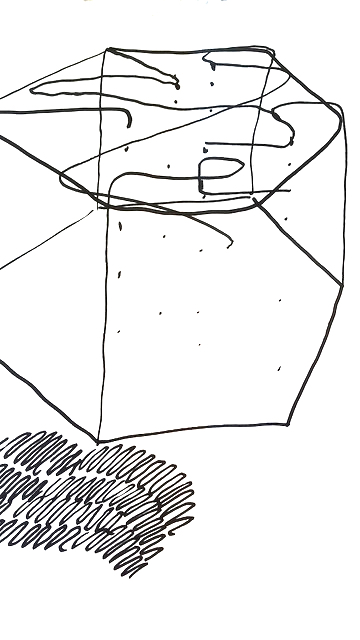

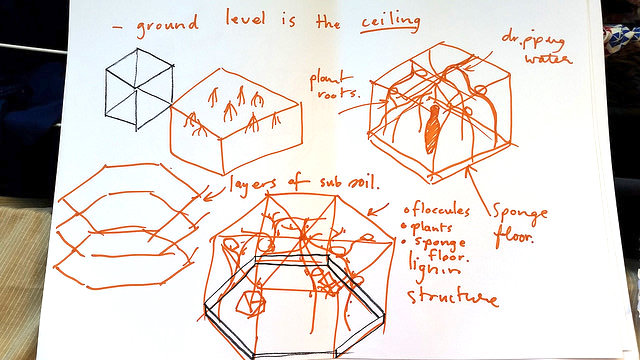

Embracing this architectural angle for humus:human suddenly made a few other things fit together. After all, humus is the architecture and the infrastructure that micro-organisms have created for their own survival. As the wonderfully entertaining soil educator Ray Archuleta “The Soil Guy” puts it in this video, “they’re building their house!” (this video has a brilliant demo of how healthy soil in a beaker holds its structure when submerged in water, whereas poor soil collapses – you should watch it). Having in mind that the soil is itself an architectural form, that it is a home, that it’s been designed for purpose, means we’re now playing with the idea of creating a sense of affinity between the human experience and the micro-organism experience.

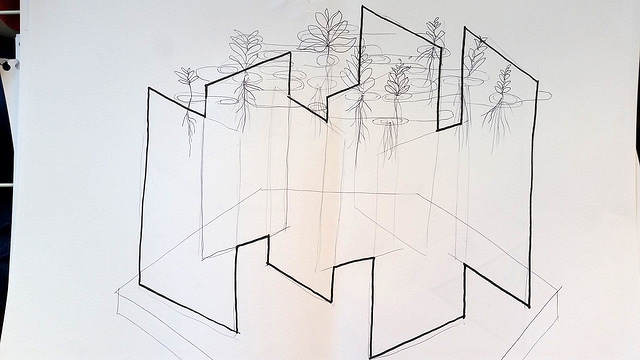

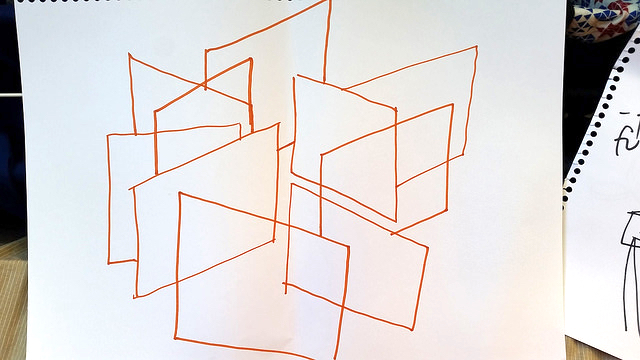

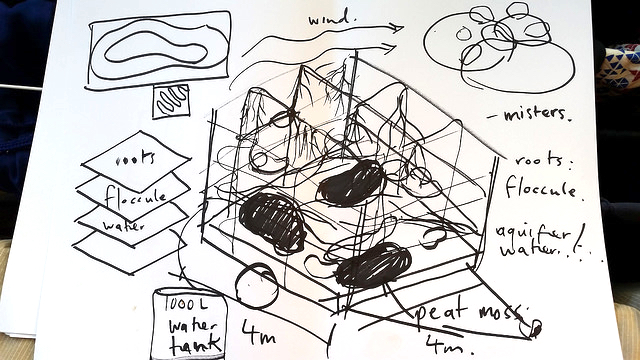

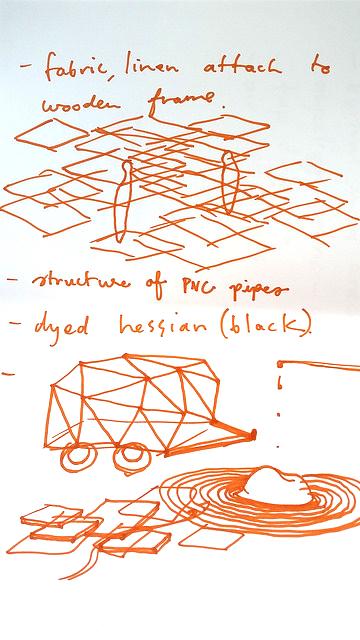

So we are now dreaming of a pavilion, maybe even a mobile pavilion that could be dismantled and reconstructed to adapt to different locations. “Humus is like a deck of cards, it will come out different every time” says Glenn – could our model could be like this too? And could it pay tribute to the bush-houses of the past, with their ‘vernacular’ style? And how do we get water in, around and through it?

Right, we’re off to the Botanical Gardens fernery. And to Bunnings for some misters...

The fernery at Sydney’s Botanical Garden. Spot the lizard!

With thanks to Cynthia Goodson for her inspirational research archived at enclos*ure blog.